Editor’s note: This is a guest post by Louis Hayes, a police officer in the Metropolitan Chicago area. It’s an important piece that discusses a topic that is often seen as controversial. Lou and I go into even more detail on this subject in episode #024 of The Crisis Intelligence Podcast. If you’re in law enforcement or emergency management, I highly recommend the listen. Tune in here. Lou and I also welcome your feedback, input and questions in the comments section below.

A crisis is a change. More specifically, bad change. And change requires a response. One’s adaptability is a measure of how effective that reaction is.

A crisis is a change. More specifically, bad change. And change requires a response. One’s adaptability is a measure of how effective that reaction is.

Crises occur in many different environments, industries, fields, and situations. They have varying levels of importance, volatility, consequence, know-ability, and duration. For example, some threats might include: financial earnings, reputation, human life, or physical assets. Some situations might be relatively steady (while still terrible), while others are unstable and can change in a moment. Some crises need immediate intervention, while others can be addressed through a slower, more analytical fashion. Every crisis is different… but they all require a response by people or organizations that are highly adaptive.

In my field of tactical law enforcement, Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) police officers frequently respond to volatile situations where lives are at stake. As a trainer of these officers, I had always struggled with how to best develop their thinking skills. However, when one of my friends attended the training course for SWAT candidates, I began codifying what it means to be a crisis decision-maker.

The Doctor in SWAT School

My friend was an emergency room physician without any police experience. In wanting to volunteer for a position as a tactical medic/doctor on a local SWAT team, he attended the two-week school alongside veteran police officers, detectives, and sergeants. When I excitingly and surprisingly heard he was the school’s top performer, I examined the similarities between responding to medical crises in the hospital emergency room and public safety or criminal issues that a police officer sees on the street. Here are the similarities I found:

- Non-linear thinking – predicting the various options or changes that can occur, the response options, and each of their consequences.

- Accuracy versus Timeliness – balancing a decision’s correctness or preference against a delay to collect and process available information.

- Prioritization / Triage – ranking and managing various problems by severity and urgency.

- Delegation – understanding whether the situation requires strict adherence to rules or demands creativity (ex: the difference between a chess player and a sports coach).

- Generalism versus Specialism – adhering to a belief that one with a broad and inclusive, but shallow pool of knowledge can be superior to the specialist’s narrow and deep skill-set.

- Stabilizing mindset – implementing stabilizing strategies to keep the problems from getting worse, and only rushing to fix them immediately when no other option is reasonable.

- Process and Systems – understanding that poor outcomes may always result when obeying or implementing time-tested processes; understanding how various parts of the whole interact with one another (ex: cause and effect).

These have become the values and traits I place on decision-makers in times of emergency. These are the factors upon which I evaluate police officers’ decisions and actions. Our officers now have an understanding of the expected behaviors and mindset required to succeed in the face of rapidly changing, tense, and uncertain situations. Yes we have parameters for our decisions, but we hold these above traits in high regard.

Incident Command

In the United States, the current emergency management system (Incident Command System; National Incident Management System) is mandated for all first responders and organizations. My fear is that it fails to account for the dynamic nature of public safety incidents, especially police incidents such as active shooters and acts of terrorism. The current ICS/NIMS program is an excellent framework for incident response once these situations are stabilized – with reduced frequency or acuity of change. But our law enforcement field is missing pieces to effectively and efficiently respond to those initial moments (maybe up to an hour?) of dynamic chaos.

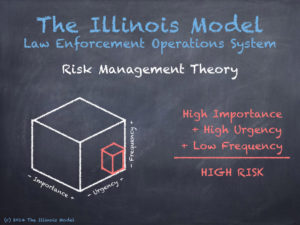

My proposal to the ICS/NIMS administrators is to adopt a foundation of problem-solving strategy or risk management. In our risk management theory, we describe and evaluate risk on a three dimensional model:

- Timeliness / Urgency – How quickly must we respond?

- Importance / Consequences – How bad can this get?

- Frequency / Potential – What are the chances of this happening (again)?

In the uncertain environment of crisis, responders must understand these three attributes of risk. We must first analyze (and lead) a crisis based on these factors before any management of resources or manpower.

Adaptive Crisis Response

I contend that adaptive thinkers respond more effectively and efficiently to crises. First off, they recognize change, and frequently anticipate it before it happens. Secondly, they use a multi-dimensional framework to analyze, quantify, and evaluate risk. Thirdly, they possess a unique set of traits, similar to an emergency room physician or a veteran police SWAT officer. Lastly, they are committed to learning from previous mistakes and stay focused on resolution and success.

Listen: The Crisis Intelligence Podcast #024 – The Illinois Model with Louis Hayes

In some industries, fields, and organizations, the above theories are serious departures from the current norms of rulebooks, binders, and checklists. (Not that those forms and lists don’t have a place in crisis management. They do. Just not at the forefront of initial response!) Some of our agencies have become slaves to these bureaucratic standards, keeping us from resolving the crisis through creativity or outside-the-box thinking. There are few standards in crisis. That’s the main ingredient of a crisis: breaking from the norm.

We need people and policies in place that defy the day-to-day operations. Policies and guidelines must allow for discretion and autonomy during crisis. And give authority to those people who have internalized these values of adaptive crisis response.

If you’d like to learn more about The Illinois Model, click here.

Louis Hayes is still figuring out when to keep his mouth shut and when to challenge the status quo. He is a systems thinker for The Virtus Group, Inc., a firm dedicated to the development of public safety leadership. Lou is a co-developer of The Illinois Model law enforcement operations system (LEOpSys) and developed several courses rooted in its theory and concepts. He is a 17-year police officer, with current assignments as a Crisis Intervention Team member, a certified Force Science ® Analyst, and a tactical medical officer for a regional SWAT team. A full compilation of articles on The Illinois Model can be found here. Connect with Lou on LinkedIn, or follow him on Twitter.

We need more Lou Hayes types in a world where critical thinking has been replaced by innuendo, rumors, hearsay, political talking points, media reporting & video editing that tells their story. I see the value of the doctor's performance as pure, unprejudiced and non judgmental in applying critical thinking devoid of peer pressure and the law enforcement culture & impact. It's a clearly informative discussion and presentation without any mention of prejudice, opinions and judgmental decisions that contribute to clouded reactions to danger and predisposed thinking. In other words let's include in the discussion the need for flexibility. Lou Hayes keep up the discussion, we have to open this pandora box if we desire to bring policing the respectability it deserves.

Thank you, Felix. I always enjoy our dialogue!